I've been obsessed with music from as far back as I can remember-perhaps from some genetic predisposition right out of the womb. Some of my earliest childhood memories are of my father's old component stereo, made up of a Garrard turntable and an ancient amplifier which took about five minutes to warm up. The exposed tubes stuck right up off the top, and as the amp came to life they emitted a warm orange glow that always gave me a safe, contented feeling.

Growing up in New York City it was hard to miss the media hoopla around The Beatles in February 1964, and The Fab Four-and in short order every variety of rock & roll-became my overriding obsession, all but obliterating serious interest in anything else. Five years later I was only more obsessed and my parents, resigned to the reality of the situation, gave me the opportunity to take my passion to the next level. In January 1969 my dad took me to the

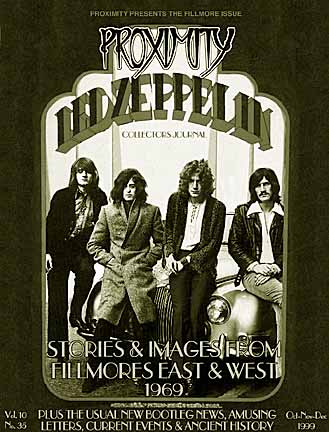

Fillmore East to see Iron Butterfly, headlining over a new band called Led Zeppelin.

Led Zeppelin became my religion and the Fillmore East my church, and that concert-plus a handful of others I attended at the Fillmore over the next two years, are the benchmark by which every musical event I've ever attended has been measured.

The neighborhood that housed the Fillmore East (previously known as "The Village Theater") was originally known as the Lower East Side, a melting pot of Jewish, Ukrainian and other European immigrants mixed with the artist and bohemian types who populated Greenwich Village immediately to the west. In the early '60s the balance shifted further to the bohemian side, and the area became known as The East Village, a colorful and somewhat seedy neighborhood populated by young, hip bohos and beatniks who sustained a thriving cultural community.

In the late '60s the East Village became the epicenter of the hippie movement in New York, and the Village Theater began presenting the "new music." Following a Cream show in 1967, the building went up for sale, and friends and associates of Bill Graham-already a successful west coast rock promoter with The Fillmore West and Winterland in San Francisco-urged him to buy it and start putting on shows.

Graham was very reluctant at first, but was finally convinced to make the trip east to see his 'Frisco friends Big Brother & The Holding Company play at the venue. According to Joshua White (who ran the famous Joshua Light Show at the Fillmore), "We took Bill on stage before we set up for Janis and he took a look at the house. As only a great promoter can do, he just went brrrm! And he counted the house. From that point on in his mind, he was convinced he could make a go of it. I saw the click in his eyes. I saw him realize this is do-able. Because here were these sleazebuckets promoting Janis Joplin with two thousand people in the house. So why wasn't he doing it?"

The theater stood on a corner and was three-quarters of a block wide. The facade and front entry area were very narrow, with stores flanking it on each side on the street, but once you walked through the narrow lobby it opened up into a beautiful hall, capable of seating just over 2600 people.

"It was like the movie theater I had gone to every Saturday as a kid in the Bronx, the Loew's Paradise" Graham recalled years later. "Soft red velvet on the walls. Carpets on the floor where you came in. Mirrored walls and a chandelier above the double balcony. A classic New York theater with great concessions upstairs and a great lobby."

By scraping together profits from his west coast venues and offering points on the new venture to Albert Grossman (manager of Dylan, Joplin, and all-around rock business titan of the late '60s) in exchange for financial assistance up front, Graham bought The Village Theater for approximately four hundred thousand dollars in early 1968 and with the help of Chip Monck, Kip Cohen and Joshua White, got to work turning the theater into a quality rock venue as only Bill Graham could do.

"I wanted a clean, well-run theater," Graham would later say. "We fixed the lobby and the concession area. We updated everything. I wanted it to look classy. So that when people came in from off the street, they would rise up to a higher level. Like when someone walks into a spiffy restaurant. Automatically, their back gets straighter. They change to fit the room. That's what I wanted to happen to people in that place."

Pete Townshend recalls ". . . sitting there [talking with Bill] in what had been called the Village Theater. We were in the stalls [seats] with the sound men running around and the roadies doing 'test. . . test. . .' Somebody came up and said, 'do you want some coffee, you guys?' And we said 'Yes, please.' The guy went away and came back with some coffees. They got us sandwiches. They brought us paper to write on. There probably was an office we could have gone and sat in but really you felt like you were sort of half in Bill's living room and also half in that quite magical place of a theater. Somehow, Bill had hit on it. He gave us dignity. We felt we weren't the pop plebes we had been when we went out with Herman's Hermits and we were told to shut up and get in the back of the bus. We were dignified people. We were artists."

A big part of Graham's vision was making sure the visuals and the audio sound system were top flight all the way. Technical Director Chip Monck (later known as 'the voice of Woodstock'), reveals that "Graham had already started this bit of brilliance. Which was, 'I'll build the best sound system available. You don't bring your fucking sound in here and stack it on the side of the stage and make my theater look like a piece of trash. Bring your monitor system if you absolutely have to, but my house system is what you use.'"

For the visuals, Graham signed on the Joshua Light Show, formed in 1967 by Joshua White, who had a background in film and attended both Carnegie Tech and the USC film school. Graham had previously worked with the freelance light show on a handful of rock concerts he promoted in Toronto.

He offered them a permanent home with headline billing at the Fillmore East for one thousand dollars per week, and sealed the deal with a handshake. Though later replaced by an outfit known as Joe's Lights, the Joshua Light Show will always be integrally linked with the venue, and during its run there became known as the state of the art-something of a lost art these days.

With staff, sound and lights all in place, Graham launched the Fillmore East on March 8th, 1968, with a show featuring headliners Big Brother & The Holding Company (with Janis Joplin) supported by folksinger Tim Buckley (father of Jeff) and blues legend Albert King. In between this and the June 27, 1971 closing night featuring The Allman Brothers, J. Geils Band and-fittingly-Albert King, the Fillmore East presented 371 evenings of concerts, most nights featuring early and late shows, and that's not counting a Tuesday night "New Groups & Jams" series they ran for a while (for only $1.50), regular open band auditions and occasional special events such as charity auctions and even movie screenings.

For me, as a young teenager growing up fifty miles north of New York City, the Fillmore was a little piece of heaven on earth. Fortunately my parents were somewhat accommodating, taking me to my first concerts there and later allowing me to go in with a friend occasionally. Seeing Led Zeppelin there twice in 1969 were some of the high points in my life, but I also felt intense frustration upon seeing the show listings including Hendrix, Joplin and all my other favorites and being unable to rally the folks to take me.

In hindsight, it's also frustrating that my young age kept me from ever catching those legendary late shows that often ran into the wee hours of the morning. I always had to be concerned about making the last train out of Grand Central by 11:30 p.m., thus it was always the 8:00 shows I attended. Still, I consider myself very fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time, and gotten a firsthand taste of this particular piece of rock history on several occasions.

The first of those occasions was the January 31st, 1969 bill featuring headliners Iron Butterfly supported by Led Zeppelin, plus a campy gospel vocal group called Porter's Popular Preachers. You can find my full scale, blow-by-blow description of this incredible concert in Proximity #10, however it should suffice to say here that it's an understatement to say Zeppelin blew Iron Butterfly off the stage that night.

From the moment we walked into the Fillmore's crowded lobby, the whole scene was blowing my impressionable young mind. Longhairs and freaks from wall to wall, the hip and the hipper seeing and being seen, and beautiful, bra-less hippie girls casually smoking joints and smiling at what must have been a stunned, open-mouthed gape on my face.

We took our seats in the lower balcony (which cost $4.00!) and watched openers Porter's Popular Preachers perform to a warmly amused response from the crowd. I recall the light show being mesmerizing, as we viewed it from eye-level in our balcony seats.

The impact of Led Zeppelin that night is forever burned into my temporal lobes-the loudest, sexiest, most exciting thing I have ever seen. Even the people who had seen the Yardbirds the previous year and already heard Zeppelin's first album were unprepared for the full frontal assault of the band live, and the crowd's response was thunderous and immediate.

They played for forty minutes before leaving the stage, returning for a loudly-demanded encore and then seemingly leaving for good with many 'thank you's' and smiles at the audience response. But the crowd wouldn't let them go. As the house lights went up people continued clapping, stomping and shouting for "more!," to the point where the light show screen, now a static shade of bright blue, flashed the phrase "more??", causing an even louder eruption from the crowd.

The lights went down and Zeppelin returned to play "Communication Breakdown," an unprecedented (or at least unusual) second encore for an early show warmup act. They finally left the stage, leaving the audience buzzing and still emitting occasional whoops as they filed into the lobby for the break or sat waiting for the now anti-climactic headlining set.

This was the stuff of legend, and I think that somehow I knew it even at the time. After that first U.S. tour, Led Zeppelin rarely, if ever, opened for a headliner again-no one would follow them!

My next excursion to the Fillmore was in March of the same year to see a folk music show-Buffy Sainte-Marie supported by Ian & Sylvia-accompanied by both of my parents (who were big Buffy fans). I relished any opportunity to spend time in the East Village, however this concert fell far short of the electrifying event I had experienced two months prior.

Later in 1969, however, I got another chance. Zeppelin's second US visit brought them back

to New York City for two tour-closing nights on May 30th and 31st. I was fortunate enough to get two tickets for the early show on the second night-$4.00 each and procured by mail order, if I remember correctly-and for this show I got to go into the city with my older friend J.R. unaccompanied by an adult!

This time things were a bit different. Zeppelin was headlining over Delaney & Bonnie (pre-Clapton, unfortunately) and jazz great Woody Herman, and the anticipation of everyone attending was high as by this time the Led Zeppelin album had become a hit and word of their previous Fillmore East shows had spread. The British quartet didn't disappoint, opening strong with the same "Train Kept A-Rollin'/I Can't Quit You" one-two punch that had left the audience in momentarily stunned silence before erupting into ovation back in January. This time the crowd was into it from the word go, cheering Plant's solo screams at the start

of "I Can't Quit You" and egging him on to greater heights.

Robert's greeting of "good evening" (already a tradition in 1969) was delivered with far more confidence and warmth than his uncertain tone four months earlier, and "Dazed & Confused" was greeted with an enthusiastic response from the crowd, which also broke into spontaneous applause at several points during the song.

The set varied only a little from what was played in January, with the show-stopping "You

Shook Me" performed earlier and of course different improvisations inserted into "How Many More Times." The early set I saw also omitted Bonham's crowd-pleasing "Pat's Delight" drum solo, however this was replaced by the stunning virtuosity of Jimmy Page on "White Summer."

Plant's announcement of "a thing featuring Jimmy Page" brought a cheer, and Page sat on a chair alone at center stage. The crowd's excitement mounted as he hunched over his open-tuned Dan Electro, exploring the seemingly limitless improvisational possibilities of the instrument with his dark hair completely covering his face. The resulting standing ovation was deafening.

While it lacked the sheer unexpected elation of my experience seeing the band in January, the performance was equally mind-boggling and of course further assured my devotion to the band. The saddest thing about my second Led Zeppelin concert is that J.R. and I had to leave early to catch the aforementioned last train out of Grand Central Station. My most vivid memory of the show is pausing at the very front of the balcony for a few moments as we made our way out of the theater, zeroing in on a barefoot Robert Plant belting out the final lines of "How Many More Times" with absolutely astonishing power.

This was Led Zeppelin's last Fillmore appearance. They quickly outgrew the small halls and future Zep concerts required visits to Madison Square Garden and the Nassau Coliseum, which I happily made. Some of these were great shows, though none had the intimacy or impact of those first dates at the Fillmore East.

By 1971 the innocence of the early hippie days was fading, and the economics of popular youth culture-aptly described by author Fred Goodman as "the head-on collision of rock and commerce"-were moving from the realm of the hip entrepreneur to that of the professional businessman. In short, there was big money to be made, and operations on the scale of the Fillmore East were far too small to compete.

Bill Graham announced the closing of both of his Fillmores at a press conference held in the New York theater in April 1971, citing increasing greed in the music business and changing attitudes in the audiences as his reasons.

"A few acts had started to play Madison Square Garden and I had been asked by them to do shows there," Graham recalled. "I said, 'you've got to support Fillmore East in New York,' but they could make as much doing one show at the Garden as four at Fillmore East. I would say to them, 'Do it here. It's only one more night. Two shows a night and it's more challenging than the Garden.'"

The '60s were over and with them the ideals of innocence and optimism that originally fueled the whole scene, and Graham didn't like it. His friend playwright John Ford Noonan claims "At the end, I think one of the things that affected Bill was that it was always unpleasant outside the theater at night, especially during the late show. I mean, huge guys were now the security. Several times, people were thrown through the plate-glass doors in front. Somehow, the spirit of the place changed. It became reds and wine and Grand Funk Railroad. Everyone was mean."

The Fillmore East wrapped things up on a weekend in June, 1971, with a final show for the public on Saturday the 26th featuring bluesman Albert King and Graham favorites the J. Geils Band and the Allman Brothers.

The same line-up played the invitation-only closing night on Sunday the 27th, augmented by surprise sets from Edgar Winter's White Trash, Mountain, Country Joe McDonald and the Beach Boys. "It was broadcast over the radio and it went on 'till like five or six in the morning," recalls the Geils Band's Peter Wolf. "I remember all these cab drivers listening to the show on WNEW FM in their cabs and it just went on all night. I mean, the Allman Brothers started around four in the morning. At dawn, they were still playing "Crossroads," or something like that."

"Take a good look at these people," said Graham to the crowd as he gathered his staff onstage that night, "so when you pass them on the street you'll know they've been your friend for a long time."

The building still stands today, it's upper facade clearly recognizable. Housed in what used

to be the theater's lobby is an Emigrant Savings Bank, where you'll find a series of framed collages featuring images from the Fillmore East. The rest of building contains offices. The lampost on the corner has a street sign above the one for second avenue which reads, "Bill Graham's Way."

Joshua White perhaps sums it up best of all, speaking for myself and thousands of others when he says, "I could easily have been just ordinary. By being at Fillmore East, I wasn't ordinary anymore. I had this experience that is a a part of my life. Everything I do to this day is always registered to some degree against the fact that for a brief moment, I was in a place where wonderful things happened."

The following books and publications are gratefully acknowledged for providing

quotes, pictures and information in writing this article:

For Proximity Subscription Information: CLICK HERE

![]()

Write Hugh Jones, Proximity Editor:

mrprox@mindspring.com